Free Street Theater Archive

Archive Home | Performances | Stories | Newsletters | Press | Videos

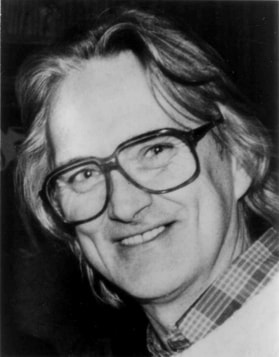

Ron Bieganski

Ron Beiganski showed up at Free Street in 1985 and worked alongside founder Patrick Henry. In the early 1990s, Ron began creating theater with teenagers living in Chicago's notorious housing project, Cabrini-Green. In those workshops, he pioneered amethod of acting training which led to the creation of critically acclaimed performances. Free Street was one of the first jobs training in the arts programs for teens in which teens were paid to participate as theater artists. Their performances toured internationally and have a had a dramatic effect on the field of community arts education. Ron became the Artistic Director of Free Street in 1995 and served in that capacity until 2011. In that time he mentored teens and teaching artists to use his philosophical framework, make it their own, and organically evolve their own creative process. Ron continues this work as a founding member of NeuroKitchen and its Artistic Director.

I showed up at Free Street to watch a performance of Free Street Toos, a group of elderly performers who talked about life and love. That was the summer of 1986. Free Street Theater was an 18-year-old community theater company founded by Patrick Henry (yes he was the direct descendant of the 'give me liberty' guy). Mr. Henry was joined by other art activists at the height of the 1960s anti-war movement. Free Street was instrumental in the DIY theater movement that took over Chicago.

I asked if there was something I could do to help and I became the rehearsal assistant and bus driver for the elders. I was Patrick Henry's assistant working with him on whatever project was going on at Free Street. A short time before Patrick died in 1989 we had a Free Street Holiday Party and my gift was to become the director of the elder company. Patrick gave me the present in an old shoe box. I wish I would have kept the letter he wrote to me.

When Partick Henry died a few months later, I started to prepare for my first rehearsal with the elders. The artistic leadership running Free Street after Partick died let me know that I was going to be replaced as director by one of the new leaders and thanks for your hard work. I was told there was a group of teenagers from the Cabrini-Green Housing project that the new leadership was not interested in working with. I agreed to begin directing teenagers at the Chicago Youth Center in Cabrini in June 1989.

Chicago Youth Center, Cabrini-Green housing Project.

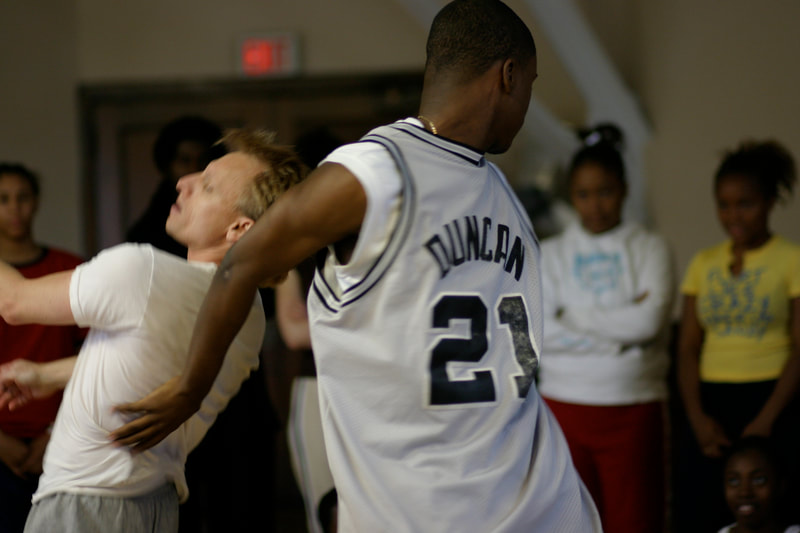

My first day of theater workshops in 1989 began with me riding a yellow one-speed bike into the cement projects and cutting through an old baseball field to get to the building where I was supposed to teach. "Get the hell inside the center" was the first thing I heard. The people greeting me were shaking their heads, looking at me and each other. I was stupid. When I walked inside, I was warned about gang snipers who would shoot from the top of the high-rise buildings- “so don’t go across the baseball field.” My response was “There’s what… up in the up? And they shoot what at the kids? Bullets?” I hadn't lived a protected life while growing up in Milwaukee, but nobody was shooting at me for trying to play baseball.

My memory of that first workshop is like the memory of rollover crash victim has when he finally wakes up and begins to look back: I was hit suddenly and spun around by thoughts of snipers, youth who were not interested, the smell of catsup and myself unprepared in most ways that would be useful in this situation.

I was put in a room where everybody at the youth center had lunch and snacks. The floor was some kind of rubber tile, sticky, smelling of ketchup and something like vomit. I introduced myself to the youth and the slow-motion car crash of my first workshop began. I struggled to get people even to take their shoes off. Thirty years later, I still work with youth who on the first day of new workshops are reluctant to take their shoes off. Difficulties are sometimes cultural, or a class idea- exposing your feet is not clean or an insult. Taking off your shoes and socks is sometimes an I don’t like my feet thing, sometimes just an “Is the floor clean” thing.

For the next 3-4 years, nobody cared about what I did with the youth. Things were beautiful as long as I did something that occupied the time of 10-20 teenagers who came into the Cabrini-Green housing project studio (lunchroom) 3 times a week. My workshops moved to an old funeral Home about three blocks from Cabrini-Green starting in 1990. We had a floor that was cleaner and the room that was all ours.

Then one of our year-end performance art pieces got noticed by a reviewer. The Chicago Reader, which at that time reviewed every theater piece that happened in Chicago, was there on opening night. We had sent the Reader information about our performance but never anticipated them showing up. We had to make a press packet as the audience came in. In 1992 “Standing out in a Drive-by World” was picked as critic’s choice by the Chicago Reader. People started noticing what we were doing. Luckily by this time my students and I could talk about our work to people wanting to see how we did what we did. My students were always my best ambassadors.

Each year we would train in theater technique and write wildly creative non-autobiographical theater pieces. Youth would stay involved in the ensemble for usually 1-3 years. I would ask for a two-year commitment so that the artistic ideas could be learned, practiced consistently and then embodied.

During the next 25 years the youth in our ensemble developed themselves and experimental performances that received 3 best-of-the-year performances, were produced twice at Steppenwolf Theater, opened a national theater conference, represented the USA at a youth theater congress in Tromso Norway, 12 tours of Europe, 45 performances at new play festivals in Europe and performances in Thailand for refugees and gangland motorbike riders. Our first workshops in Europe in 1995 started youth organizations rethinking the how, why and what their youth programming was.

The ensemble’s ardent non-autobiographical performances opened many people up to some of the problems with autobiographical victim theater. Community youth theater was mainly mining the youth for their personal stories and having performances that were intrusively very personal. Many performances by youth included violence, sexual abuse while being performed by the kid that had this abuse. We preached for more understanding of protecting a victim’s privacy. The ensemble showed that non-autobiographical work could be emotionally powerful and deal with current life without being didactic or pretending to be therapy.

Since 1986 my theater/creative process has grown and changed from continual research into how the brain functions and experiments to develop acting exercises. Every workshop is a new experiment. Even with the continuous changes, each new ensemble of students starts with us defining what is creativity and talking about how do we get to that heightened creative place.

- Ron Bieganski

(written December 2018)